Panic in Overnight Lending

Overnight Borrowing Liquidity Issues

Overnight borrowing rates have spiked unexpectedly this week, raising questions about whether there’s a looming liquidity issue in the market.

The NY Fed implemented borderline-emergency measures to inject liquidity this week. It bought $50B in Treasurys yesterday and will buy another $75B today. The basic mechanism is that the Fed will overpay a bank to buy some of its Treasury holdings. This gives the banks cash, which in turn they can lend to other banks. Liquidity. Or as some might call it, Quantitative Easing. Jay Powell won’t call it that, but some might…

The headline culprits according to the talking heads I trust the least:

- Corporate tax bills – money was withdrawn from bank and money market accounts to pay quarterly and annual taxes (Monday was the corporate extension deadline), which reduced the amount available as deposits to banks

- Last week’s Treasury auction – the cash payment for the $78B T auction was due yesterday and banks typically pay for their Treasurys by borrowing in the overnight market

Call me a cynic, but while these may be contributing factors, are they really to blame for a liquidity event that caused some borrowing rates to spike 3x? We were hearing from traders that repo rates got as high as 8% – 10%. Think about it – you are contractually obligated to buy something (or pay for something), you will pay 10% for one night of borrower if you have to, right? How high does the interest rate need to go before you willingly default on whatever it was that required you to go borrow in the first place?

Banks don’t borrower the way consumers borrower. They fund day to day operations through overnight loans as their deposits fluctuate, sort of like a line of credit they draw on and repay quickly. These are called repos (short for repurchase agreements). Repos are generally overnight loans backed by Treasurys as collateral.

Some days banks need to borrow, some days they can lend. But if they don’t have cash available (or in a financial crisis meltdown, don’t want to lend), then borrowers have to pay a higher interest rate to entice them to lend. This most commonly happens at quarter and year end when banks hoard cash for the balance sheet snapshot. What is unusual is that it is happening mid-month.

Banks are required to maintain a set reserve (generally 10%) of their deposits at the Fed. Anything above that amount is referred to as excess reserves. If Big Bank has $1T in deposits, it must maintain a balance of $100B at the Federal Reserve.

After the crisis, the Fed wanted to encourage banks to keep an even bigger cushion, so it began paying Interest on Excess Reserves, or IOER. The Fed might say, “Dear Big Bank, you are required to keep $100B with us, so we aren’t paying you for that. But we will pay you 2.10% on any amount above that.” IOER. It usually is set in the same range as Fed Funds to avoid arbitrage scenarios. And it incentivized banks to keep a bigger cushion of cash.

It worked. Banks were getting risk free interest from the federal government, so they maintained larger cash balances at the Fed. But it’s also at least partially to blame for why banks might be reluctant to lend from time to time. “Why loan money to Risky Commercial Real Estate Borrower when I can get a risk-free return from Uncle Sam each and every night?”

Extrapolate that even further, and banks might ask themselves, “Why lend to a fellow bank at Fed Funds when I am getting 2.10% from the Fed?”

This dilemma has been exacerbated by the flattening yield curve. It’s easy to justify getting 2.10% from the Fed while maintaining flexibility when the alternative 10 Year Treasury is yielding 1.50%. And when the alternative Risky Commercial Real Estate Borrower is borrowing at a spread over 1.50%.

Easy fix – lower the IOER. If you remove the incentive to maintain excess reserves, it will instead encourage banks to lend, right? Yes, in fact the Fed will likely do that at today’s meeting.

But there’s a catch…well, two actually.

- Panic – during periods of stress or fear, do you really care that the return from the Fed is 1.75% instead of 2.0% from a fellow bank? I was at Wachovia when it went under and I can assure you there was no amount of interest we could have paid to other banks to entice them to loan to us, even overnight

- Lowering IOER only helps if banks have excess reserves to begin with

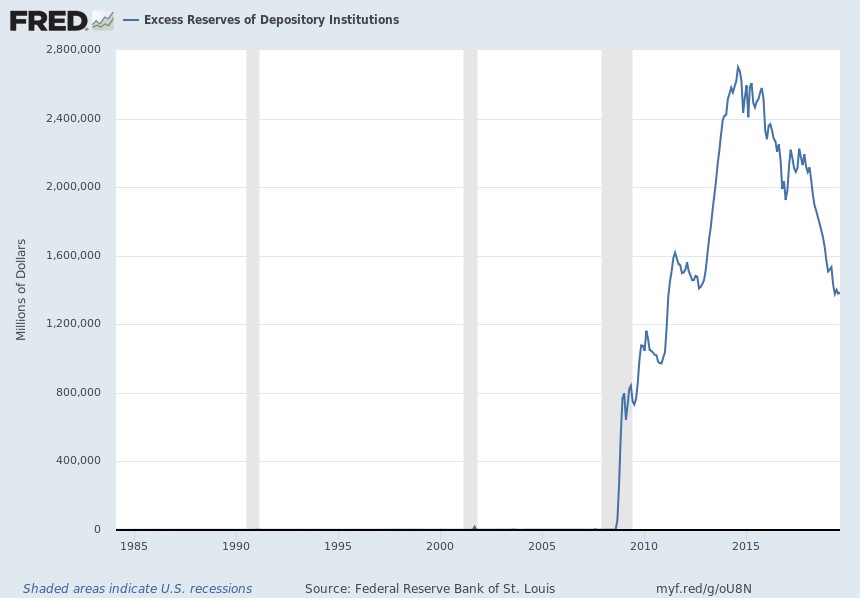

Reverse QE (aka Balance Sheet Normalization) has reduced the cash banks have available because the Fed stopped buying their Treasurys each month. Here’s a graph from the St Louis Fed that shows how much excess reserves have fallen recently.

Fewer excess reserves coupled with liquidity fears lead to a spike in overnight borrowing costs. It remains to be seen whether that will resolve itself quickly or if this is the start of a scary trend.

The Real-World Implication

For now, our lives probably don’t change much. But the risk of a liquidity-driven downturn has increased substantially. It’s not a definite, it’s just a greater possibility.

Without liquidity, the system grinds to a halt. Sure, Big Bank may pay 10% today just to fulfill their legal obligation, but what changes do they make going forward? “Hey, loan allocations need to be scaled back because we may need that cash instead.” Now imagine the ripple effects from decisions like that…

“I didn’t even know what a repo was before this morning, now you’re suggesting it might impact my ability to get a loan?” – Frustrated Commercial Real Estate Borrower.

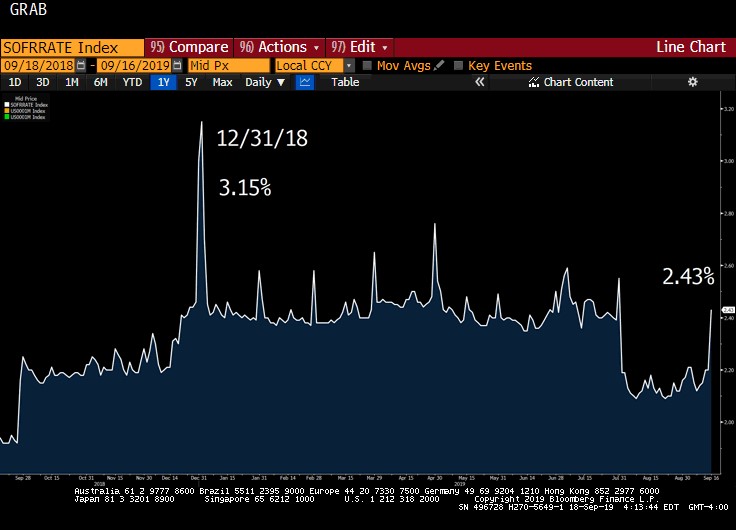

Actually, I can think of one prominent repo rate you might have known about before today…SOFR. The presumptive replacement for LIBOR is a repo rate. Readers of this newsletter know I am very skeptical about SOFR replacing LIBOR in 2021, and one of my primary reasons for this skepticism is that it swings wildly.

On the one hand, the fact that LIBOR never flinches during periods of volatility like yesterday confirms the reason why the regulators want to move away from it. It feels…not accurate…

On the other hand, market driven securities are subject to market driven volatility, which can create chaos.

Here’s a graph of SOFR over the last year. Notice how it spikes at quarter and year end when banks don’t want to lend out cash to other banks because they are about to take a snapshot of their balance sheet. It spiked to 3.15% on 12/31/18.

Yesterday, it spiked to 2.43%. LIBOR is still cruising along at 2.05%…

The first implication for a SOFR-based loan is that if you have a payment reset on that day, your monthly bill could spike for no good reason.

But that’s not why I don’t believe SOFR will replace LIBOR in 2021. That can be addressed by averaging the daily resets.

More importantly, this inconsistency makes it difficult for traders to extrapolate a forward curve. How can you accurately price a swap or a cap with those sort of spikes?

As one trader put it to me, “How would you sell a cap at 2.00% on that graph?” Good question.

I wouldn’t. And neither would you. You can’t account for the spikes.

Oh Yeah, There’s an FOMC Meeting Today

Who knew the FOMC 25bps rate cut today would not be the headliner?

Markets have an 83% probability of a 25bps cut, and a 17% probability of a 50bps cut.

Count me in the 25bps cut camp. But more importantly, what signals does Powell send about future cuts? The market wants a dovish Fed, and if his comments are interpreted as hawkish (or, at least not dovish enough), the market may puke.

The liquidity issues this week will only magnify the response if the market believes the Fed is tone deaf.