Buying a Cap Below the Floor? Learn About the Flooridor

If you’ve been reading our publications over the past few weeks, then hopefully we’ve hammered home the importance of negotiating your loan floors and how you can avoid missing out on lower interest expense if the Fed cuts sooner than expected. But what if you’re looking to lower your rate today instead of simply hoping that rates begin to fall? Some borrowers have accomplished this by purchasing an interest rate cap struck below where floating rates are expected to go, effectively prepaying some interest up front and buying down the rate day one.

However, before you start shopping for a 1.00% cap, many loans have floors that are set at or near the floating rate at closing, meaning you could be capping your rate below the loan floor. If that’s the case, the hedge might not have the effect on the rate that you’re expecting. Before we get into the details, here’s what we’ll be covering in this resource:

- How capping beneath the floor behaves when rates fall

- How you can solve that problem by buying out the floor

- How you can solve that problem at a lower up front cost by buying a flooridor

Here, we’ll just be covering the specific use case scenario of capping beneath the loan floor. So, if you haven’t already, be sure to read our resource on buying out the floor for an overview on floor and flooridor mechanics.

The Problem with Capping Below the Loan Floor

Here’s the executive summary of how your rate behaves when you cap SOFR below the loan floor:

- SOFR is above the loan floor – Your rate is equal to the cap strike

- SOFR is between the cap strike and the loan floor – Your rate begins to increase above the cap strike

- SOFR is below the cap strike – Your rate is equal to the loan floor

Now, let’s take a look at why that is. For these examples, we’ll assume the loan floor is set at 3.00% but the borrower is attempting to buy down the rate by purchasing a cap struck at 1.00%.

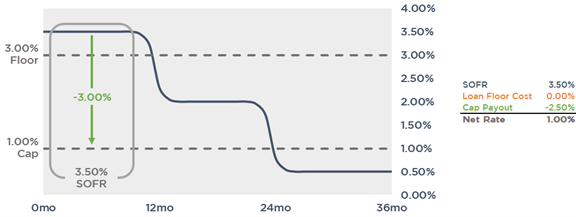

SOFR is Above the Loan Floor

In this scenario, SOFR resets at 3.50%, well above the 3.00% loan floor, which isn’t coming into to play. The cap pays out 2.50%, bringing the net rate down to the cap strike.

Takeaway - So long as SOFR remains above the loan floor, the cap effectively lowers the borrower’s rate.

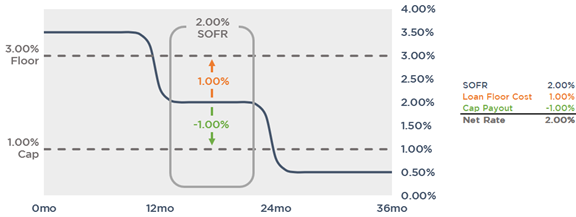

SOFR is Between the Cap Strike and the Loan Floor

SOFR resets at 2.00%. In this scenario, the cap is still paying out the difference between SOFR and the cap strike, but the loan floor is now working against the borrower. The loan floor is costing the borrower an additional 1.00%, which negates the 1.00% payout from the cap. The rate nets out to be 2.00%, which is above the cap strike.

Takeaway - As SOFR begins to fall beneath the loan floor, the cap starts becoming less effective at bringing down the borrower’s rate since the loan floor erodes part of the cap payout.

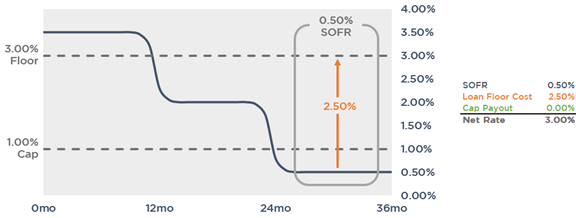

SOFR is Below the Cap Strike

In the last scenario, SOFR resets at 0.50%. Here, the cap isn’t providing any protection since SOFR has reset beneath the strike. However, the loan floor is costing the borrower 2.50%, bringing the borrower’s net rate all the way up to 3.00%, which is the loan floor.

Takeaway - If SOFR falls beneath the cap strike, the cap provides no protection and the borrower’s effective rate is the loan floor.

The Solution – Buying Out the Floor

To remedy the issue of the cap insufficiently negating the impact of the loan floor, you could purchase a separate floor contract that pays you when the floating rate falls beneath the loan floor (aka buy out the floor). Just in case, here’s the link to that buying out the floor resource again.

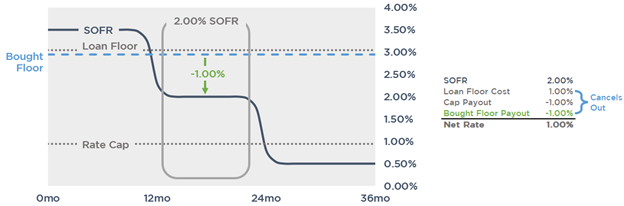

Let’s look at the same scenario as above but assume the borrower enters into a separate floor contract struck at 3.00% that pays them for any amount SOFR falls beneath the strike. The graph below illustrates how this would play out if SOFR resets at 2.00%.

Because SOFR is below the loan floor, it’s coming into play and costing the borrower 1.00% in additional interest. The cap is paying out but, because it only covers amounts above actual SOFR, it’s only providing 1.00% in protection, which isn’t enough to bring the rate down to the borrower’s intended level.

This is where the separate floor contract comes into play.

Because the strike matches the loan floor, it negates its impact completely. In other words, the loan floor is offset by the floor contract and the cap is able to function as if there isn’t a floor on the loan to begin with.

The end result? The borrower’s max rate on the loan is cap strike + loan spread, regardless of where SOFR resets.

The Cheaper Solution – Flooridor

Because buying out the floor negates the impact of the loan floor entirely, the rate could fall below the cap strike. If your goal was simply to bring your rate down to the cap strike, then you’d be over-hedged by buying out the floor.

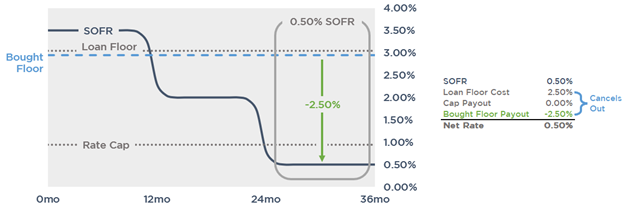

Here’s how our example structure would behave if SOFR reset at 0.50%.

In this scenario, the bought floor pays out past the cap strike, bringing the rate all the way down to 0.50%, below the 1.00% target.

If your intent was only to bring the rate down to the cap strike, you could proceed a couple different ways:

- Just leave it as is – If the floating rate falls below the cap strike, you benefit from the lower effective rate.

- Sell a floor back to the hedge provider at the cap strike – This negates the overpayment if the floating rate falls below the cap strike and, in exchange, the value of the floor you sell back is netted against the upfront cost of buying out the floor, saving on hedging costs.

Recall that simultaneously buying a floor and selling one back at a lower strike creates a floor corridor or, as we call it, a “flooridor.”

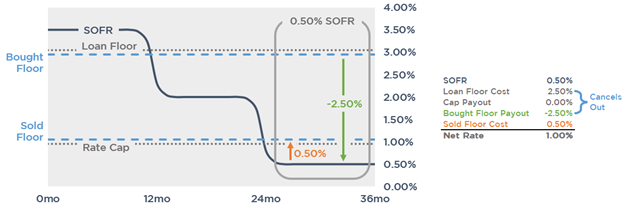

Let’s go back to our example structure but add in a sold floor at the cap strike.

The net effect is a reimbursement exactly equal to the difference between the loan floor and cap strike. Effectively, your rate isn’t able to fall below the sold floor strike but compared to simply buying out the floor, a flooridor is cheaper up front since the value of the sold strike is netted against the cost of the bought strike.

Conclusion

We’ve thrown together a bunch of moving pieces, so here are the main takeaways:

- If you’re looking to buy down your rate with an aggressive rate cap, it may not have the impact you’re expecting if the cap strike is below the loan floor.

- If your intent is simply to negate the impact of the loan floor and retain the ability to float below the cap strike, you can simply buy out the floor by purchasing a separate floor contract with a strike matching the floor.

- If your intent is only to buy your rate down to the cap strike and you don’t necessarily need to retain the ability to float below the cap, you could purchase a flooridor. The flooridor would reimburse you for just the difference between the loan floor and cap at most, but you’ll have saved the value of the sold strike up front.

If you’re looking at placing a cap beneath your loan floor and have questions about the mechanics of using a floor or flooridor to ensure the effectiveness of your hedge, reach out to the experts at pensfordteam@pensford.com or (704) 887-9880.